What can Lord of the Rings teach us about naming?

Recently I ran a hybrid workshop on linguistics and naming for my team at Northbound in our Seattle office. The topic: Constructed languages and naming in the world of J. R. R. Tolkien. Really it was an excuse for me to roll out my hobbit hobbyhorse, and like a true hobbit-at-heart, it was an excuse throw an unexpected party.

We started the workshop enjoying some homemade meat pies and mushroom pies (cue Pippin: "Mushrooms!") made by my lovely wife, and “lembas donuts” conveniently delivered to the bakery next door straight from Rivendell itself.

Actual Wizards: Workshop with the team at Magic: The Gathering

Concurrent with our internal workshop, our clients at Wizards of the Coast were preparing to launch their first Tolkien-themed set for Magic: The Gathering, Tales of Middle Earth (release date: June 23). So we thought, why not bring in some actual Wizards to the conversation! As awesome creative partners, the MTG team was totally game, and we ran a couple of linguistic workshops with Tolkien-inspired naming exercises. We focused on how inspiration gleaned from Tolkien can fuel character and naming development. MTG had a team of about 26 from their creative studio join a virtual workshop with Northbound, and the collaboration was magical. We then presented back the results of the workshop during a companywide Wizards of the Coast presentation on the eve of their Tales of Middle Earth pre-release.

Here are some of the key points from those workshops.

Tolkien the man

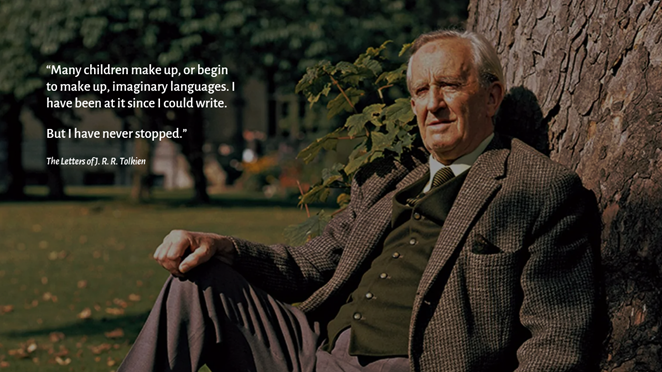

It’s probably safe to say no one has made a bigger impact on the fantasy genre of literature than J. R. R. Tolkien. But what became an epic fantasy world began simply with language. Making up languages was Tolkien’s hobby from childhood.

In a letter to his son Christopher in 1958 he said, “[The Lord of the Rings] was an attempt to create a world in which a form of language agreeable to my personal aesthetic might seem real.” Before writing his epic novel, Tolkien was a research associate for the Oxford English Dictionary and a Professor at Oxford University, where he established himself as a reputable scholar of Old and Middle English.

In addition to developing phonology, grammar, syntax, lexicon for a full-fledged language like Quenya (an Elvish language), he gave it a history and a mythology. His tales of Middle-earth were simply the vehicle through which he could share his linguistic creations.

Tolkien’s languages

So, how many languages did Tolkien actually come up with? Probably somewhere between 2 and 20, depending on your definition of “language.” Writer Helge Kåre Fauskanger created a compendium of Tolkien languages called Ardalambion, in which he explains the following: “If we consider the ‘historical’ versions of the tongues that are relevant for the classical form of the Arda mythos, Tolkien developed 2 languages that are vaguely ‘usable’ (in the sense that you can compose long texts by deliberately avoiding the gaps in our knowledge), named roughly 8-10 other languages that have a minimum of actual substance but are in no way usable, provided mere fragments of at least 4 other languages, and alluded to numerous other languages that are either entirely fictitious or have a known vocabulary of only one or a very few actual words.”

Here is a (small) sample:

Quenya: An older Elvish language, in Middle-earth it’s akin to our Latin – a scholarly pursuit, a formal language used for writing and record-keeping, and used for formal royal names. Tolkien was largely inspired by Finnish, Latin, and Greek.

Sindarin: Almost like Quenya’s simplified form, it’s the daily language of elves by the Third Age, and the language that is meant by the more common term “Elvish.” For this one, Welsh was Tolkien’s inspiration.

Khuzdul: As Sam Gamgee remarks, “A fair jaw-cracker dwarf-language must be!” By their own will the Dwarves resisted the change of their language, and the language diversified and changed so slowly, ‘like the weathering of hard rock compared with the melting of snow.’ Dwarves are a private people, and so they have an inner name and an outer name. “Gimli” is an outer name for example, and they wouldn’t reveal their inner names to outsiders. Its real-world inspiration according to Tolkien was Semitic languages like Hebrew and Arabic.

Entish: The sonorous, rumbling and ancient language of the Ents, was a slow and thoughtful language for a slow and thoughtful people, in which words and names told the story of the things they described. This is perhaps part of the reason for the Ents’ shyness about names, considering their own Entish names to be private things only to be told to trusted friends.

Black Speech: The dark tongue of Mordor, in a way it’s a doubly constructed language because in the world it was actually created by Sauron himself as a constructed language to unify the servants of Mordor, like an evil Esperanto. In its structure it’s a sort of debased form of Quenya.

Tolkien’s naming

It seems there’s a sense that the names in Tolkien’s world just sound right, in many cases. There are many reasons for that, but one of which is because he actually did draw inspiration from real world languages. So for English speakers at least, some of the names echo in the halls of our own tongue, ringing back some sort of familiarity – a nostalgia for something we haven’t personally experienced.

Tolkien was also fantastically consistent in his own languages, from which he created new names of people and places derived from his own systems. Think: Mor-ia, “Black Chasm” → Mor-dor, “Black Land” → Gon-dor, “Stone Land,” and so on.

His languages, particularly Quenya and Sindarin, were highly systematic and coherent, like a natural language might be, even with its own history of sound changes and dialect shifts over time.

Sound-flavor

Then we looked at the final naming method Tolkien uses, which is perhaps most directly applicable to the work we do in brand naming.

Exercise: Look at these two pieces of text side by side and note any observation about these two invented languages.

Notice any patterns? What kinds of sounds are you seeing repeated? Or maybe you notice the way words are put together? Not to mention the vocabulary choices.

Linguist Joanna Podhorodecka analyzed samples of these two languages and tabulated the proportions of vowels and consonants, as well as the types of vowels and consonants that appear in each.

Over 10% more consonants appear in orcish Black Speech, giving it less of a sonorant feel as opposed to the elvish Sindarin. Far more vowels and liquid sounds in Sindarin. This is what Tolkien called lámatyáve, a Quenya word meaning “sound-flavor.” Elsewhere he called it phonetic fitness, and others call it sound symbolism or phonesthetics.

We notice two things when comparing the sounds of each language:

Front vowels, that is, vowels that are articulated with your tongue at the front of your mouth, like [i] and [e], are more common in Sindarin, as opposed to back vowels like [o] and [u] are more common in Black Speech.

Black Speech contains more voiced consonants, that is, constants that are articulated with your vocal folds activated. You can notice the difference yourself if you pronounce “sssss” and then “zzzzz.” They’re the same sound, just the [z] sound activates the vocal folds.

Why this difference? Linguists have been debating the idea of the connection between sound and meaning for centuries. Recently (meaning, about 100 years ago), the speculation was brought into the context of brand naming.

Vowels. Study after study found that words – particularly invented words – that use front vowels sound lighter, faster, brighter, smaller, and so on. Research participants rate words with back vowels as bigger, slower, heavier, darker, more ominous. Think of a dog’s yelp vs. a dog’s growl. It could have something to do with anatomy: bigger, longer vocal folds create a deeper more resonant sound, and so a creature with a deep voice must be big and potentially a threat. That’s one theory.

Consonants. When studies asked participants which motorcycle brand sounded faster, Valp or Galp, overwhelming the answer was… well you can probably guess, right? The [v] sound is a voiced consonant, meaning your vocal folds are activated when pronouncing it. What does that mean for the brand? It might suggest activity or energy, since your throat is literally vibrating when you say it.

Are these trends universal across all languages? Some might be. There’s debate about how universal these patterns are – but they’re certainly true for English speakers. Bringing it back to Tolkien, who as an English-speaking linguist was aware of these kinds of sound patterns, he used language both to convey a sense of distance from home (home = English = the Shire) and to say something about the people who spoke it. Elves are light, airy, sonorant, elegant, sophisticated. Orcs are brutish, rugged, ominous, dangerous.

And as brand builders, we can use these sound patterns to our advantage when creating new names. Is power or energy an attribute the brand wants to convey? Something light and fast? Smooth and elegant? We can use the principles of lámatyáve to help names carry these unspoken messages into the market.

Interested in talking more about Tolkien? Reach out and I can prepare an unexpected workshop with your team.